[ad_1]

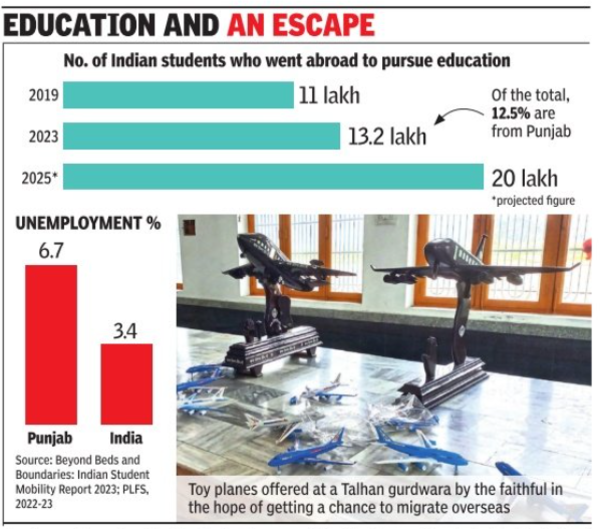

In a state where the measure of one’s success depends on how many of your relatives are ‘NRIs’ (non-resident Indians), the gurdwara gets thousands of toy planes every day which are later distributed to children who visit the shrine.

While the gurdwara has never claimed any such divine powers to issue visas, believers like Ravinder Kaur from Raya city in Amritsar district keep hoping for a miracle. Her nephew’s visa has been rejected thrice by Canadian authorities. He filed his fourth application for a tourist visa in the morning and Ravinder brought him to the gurdwara, an hour away from their home, for blessings. “He is a plumber. He has all the required documents and has even shown property in his name. But he has been unlucky so far. I thought coming to the gurdwara will help,” said Ravinder.

She has reasons to be hopeful. Her son had applied for a visa to Australia and Canada in 2019 and visited the gurdwara. “He got acceptance letters from both. He settled for Canada and works as a cab driver there,” said Kaur. Now all her children, two sons and a daughter, are in Canada or Australia. She says the travel agency in her city sells 150-200 air tickets every month to these two countries.

Talhan lies in the Doaba region known as Punjab’s NRI belt. Every street corner advertises English language exams like IELTS necessary for admission in foreign universities. Agencies pitch their “visa first, pay later” or “full family visa guaranteed” schemes through billboards, insta reels and YouTube videos. There are tall promises of converting tourist visas into a work permit, “full packages” that include admission in a college to getting a job that costs several lakhs.

But the harsh truth is that not everyone is flying high. For every successful application, there are thousands that are rejected. So, how about those who are left behind?

Punjab, once the poster boy of the country’s success in self-reliance, has crashed and burnt, and how. According to a study, the state’s agriculture grew by 5% from 1971 to 1986 even as Indian agriculture grew at 2.3%. Between 2006 and 2014-15, its output grew by only 1.6% while India averaged 3.5%. It has stagnated since then. The state’s GDP too has nosedived. It topped all states in 1981 and was ranked fourth in 2001. It is currently ranked 16 with a GDP of about Rs 8 lakh crore.

With agricultural growth stagnating, few youngsters want to become farmers. Salvinder Singh, a farmer from Ajnala’s Jagdeep Khurd village, an hour away from Amritsar, admits there are no young men left in his village. “There is no work.

Agniveer scheme has blocked their chances for an army job. Farming cannot sustain our families anymore. Whoever could afford it have sent their children abroad. In frustration, children are tempted to take chitta (drugs),” he said.

Most young people feel ignored by po litical leaders and frustrated by the lack of employment opportunities in the country. Industry too has given Punjab the miss. Once famous for production of sports goods, Ludhiana’s industry has slowly withered away. Federation Of Punjab Small Industries Associations president Bandish Jindal says states like UP, Gujarat and Andhra Pradesh have beaten Punjab by providing cheap land, labour, and power. “The input costs in Punjab are so high that they make our products unviable,” he says. If competition from Chinese products was not enough, closure of trade with Pakistan has also hit businesses badly. Farm protests have created supply problems.

In an example of how states have leaped forward in progress where Punjab has barely crawled, Jindal says GST collection in Haryana and Punjab in 2016 was Rs 17,000 crore and Rs 16,200 crore, respectively. “Now Haryana has a collection of Rs 80,000 crore whereas we are at Rs 20,000 crore,” he says.

This is also reflected in govt data for 2022-23 that recorded an unemployment rate of 6.7% in the state as compared to the national average of 3.4%.

Lack of employment opportunities is a major talking point in every poll rally, but whether it is BJP, Congress or AAP, there is a public perception that these are empty promises and little has changed on the ground.

Twenty-four-year-old Ishika (uses one name) who is pursuing post graduation in Punjabi language in Amritsar, is already worried. “I still have a year to complete my studies but the thought of getting a job is so stressful. There appears to be no options for young people who have stayed back,” she says. Ishika’s brother and her cousin have moved to Russia and Canada, respectively, and are unlikely to come back.

In Jalandhar’s Model Town, 22-year-old Neha (uses one name), who started as a sales staffer soon after finishing school, was lucky enough to find a job but without much of a future. As she folds clothes and hangs them back in their racks, she knows she will never be able to afford the international brand she works 12 hours for. She can see the gleaming SUVs zipping past her on the road outside. “My husband is also in a sales job and we both work long hours but there is hardly enough to meet expenses and there is no scope for growth,” she says.

Neha tried her luck and filled forms for the police and railway recruitment exams but was not successful. Every year, lakhs appear for a few thousand govt posts which are quickly filled up.

Punjab Travel Agents Association former president Kuldip Singh Hayer, who runs Universal Travels in Jalandhar city, says, “Degrees in India, whether public or private colleges, are easily available but they have no value. Unemployment is so high that despite challenges like large amounts of money required, people are desperate to go overseas.” The recent capping of visas by Canada for instance is likely to hit students who desire to go abroad. Attacks on students and stories of hostility towards Indians haven’t helped.

Ishika says, “Politicians don’t talk about jobs and even when they make promises, they rarely ever come through. Can you blame anyone if the line at the IELTS coaching centre is longer than the one at school?” she asks.

[ad_2]

Source link