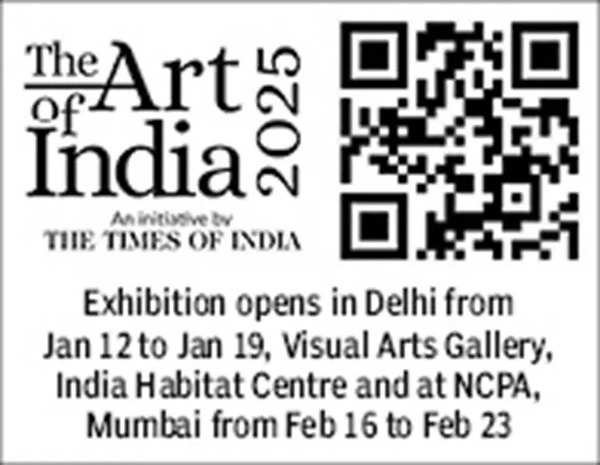

In the country’s busy art calendar,

The

When the economy is booming, the art market always sees an upsurge, and this is what is happening in India right now. In my opinion, it is always a good time to host an art event. I would like to make a clear distinction between other fairs and initiatives like The Art of India (AOI). Those are more like trade fairs where the organisers either cobble together or select successful, well-known art galleries from India and abroad, and provide commercial spaces for selling. However, AOI is very different from such commercial art fairs in the country. For one, it is a completely curated arts initiative telling the story of Indian art, including traditional, sacred, modern, contemporary and indigenous. It showcases both the tangible and intangible heritage of the country, informing and bringing in a thoughtful, reflexive display of art practices.

While showing the masters, it is also showcasing tomorrow’s blue chip, in addition to the cultural diversity and the plural culture of India. The Art of India is more about informing the general public about the history of Indian art and the cultural signifiers of Indian artistic practice.

You have introduced a new section called Hidden Gems. Can you tell us about that?

I have used ‘Hidden Gems’ as a deliberate title. In this country of 1.4 billion, there are thousands of art graduates not only from well-known art institutions but also those working outside the more structured art space. There are also numerous self-taught artists, as well as folk and tribal artists, who have been trained in the traditional ‘guru-shishya’ parampara. These artists are important culture bearers and carry within themselves vast knowledge systems and Indic traditions through their artworks. I have travelled the length and breadth of the country, seeking out artists who work quietly and consistently. These artists often live in the margins, and change often begins there, taking a while to reach the center. It is these artists — some of whom have been overlooked, such as master printmaker Haren Das — that I aim to make more visible.

There are several artists from Kerala who have made it big nationally, thanks to some great fine arts colleges and the Kochi Biennale. You attempt to shine a new spotlight on artists from Tamil Nadu. Can you elaborate?

Kerala enjoys a unique status, and I may compare it to Bengal. Artists from Kerala not only possess skill but also benefit from a rich legacy of mural traditions, temple architecture, and cultural dance forms.

Establishment of the first-ever Indian biennale, the Kochi-Muziris Biennale in 2011, also gave a huge boost and a fillip to artists from the region. I feel, however, that Tamil Nadu, despite its rich artistic legacy from the Government College of Arts and Crafts and its architectural heritage in places like Thanjavur, has somewhat fallen into the shadows. It was consciously decided to include artists from Tamil Nadu who have their own distinct artistic language but have somehow been overlooked.

In the last edition of The Art of India, the section on indigenous art drew much appreciation. How have you improved on it this time?

Folk and tribal artists provide a deep cultural connection to the essence of Indian tradition, philosophy, and myths. Indigenous artists are great storytellers; they are also guardians of ecology. Indian indigenous art, to some extent, is the most significant reflection of the spirit of India. This year’s AOI will introduce some tribal art that has not previously been seen on art platforms or in galleries.

In this time of war and conflict, how important of a role does art play?

War, conflict, migration, political unrest and climate change have made it an increasingly challenging world. I believe art uplifts, informs, builds cross-cultural bridges, and unites people through the heart. It erases man-made borders and serves as a panacea for much of the conflict.